A comprehensive clinical study confirms the molecular link between microcephaly caused by Zika and ANKLE2 variants

An international team of researchers report a comprehensive clinical phenotypic and genotypic analysis of the largest cohort studied so far of patients with ANKLE2 gene variants. A few years ago, mutations in ANKLE2 were identified as a cause of microcephaly (‘abnormally small head’) in infants. The findings were published in the Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

The study was conducted by Dr. Ajay Thomas, a child neurologist at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine, and Dr. Ghayda Mirzaa, principal investigator at Seattle Children’s Hospital, with contributions from investigators at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute (Duncan NRI) at Texas Children’s Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine.

“This study originated a few years back when I was a first-year Child Neurology resident at Texas Children’s Hospital. Through molecular testing, I found variations in ANKLE2 gene - a relatively unknown player at that time - as the primary genetic cause for microcephaly in a patient,” said Dr. Thomas. “Right around that time, Drs. Hsiao-Tuan Chao and others in the laboratory of Dr. Hugo J. Bellen, professor at Baylor College, in collaboration with the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, were experimenting with the idea of using fruit flies to diagnose and dissect the underlying genetic causes of rare childhood neurologic disorders. When I learned Dr. Nichole Link, a postdoctoral fellow in the Bellen lab at that time, had identified the molecular mechanism by which ANKLE2 and Zika mutations caused microcephaly, my interest was immediately piqued”.

Dr. Thomas initiated the present study with Drs. Chao, Link, and others in the Bellen team to gain deeper clinical insights into the similarities and variations in the clinical presentations of microcephaly caused by ANKLE2 mutations versus that caused by the Zika virus.

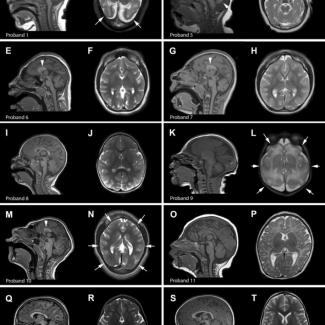

In the current study, Drs. Thomas and Mirzaa established a wide network of clinical collaborators from all over the US and abroad through which they were able to identify twelve individuals with microcephaly and variants in the ANKLE2 gene. They analyzed the patients’ clinical data such as phenotypic evaluations, developmental assessments, anthropometric measurements, and brain imaging tests. They also investigated the biological function of a subset of identified ANKLE2 variants using fruit flies.

With this comprehensive analysis, they found that all patients in this cohort had developmental delays, with delays in speech and language acquisition being the most common and a majority of them also exhibited a broad range of brain abnormalities. Interestingly, a majority of patients in the cohort also had abnormal skin pigmentation, which is not seen in Zika patients.

“Our previous study using fruit flies had demonstrated that microcephaly caused by Zika and ANKLE2 mutations occur via the same genetic and molecular pathway,” Bellen said. “This clinical study is consistent with that and confirms that patients affected by these two conditions show similar symptoms. However, we are intrigued by some unique features seen only in ANKLE2 patients (such as abnormal skin pigmentation), which will need further in-depth mechanistic studies to explain.”

“Based on the earlier studies, it was commonly thought that ANKLE2 mutations usually manifest in severe microcephaly whereas our study with a larger cohort demonstrates that ANKLE2 mutations can cause a wide range of severity in microcephaly among patients, some having more a severe form than others,” Thomas said.

“This study highlights the importance of performing a thorough molecular diagnostic evaluation in individuals presenting with microcephaly,” added Dr. Chao, also a child neurologist at Texas Children’s Hospital and assistant professor at Baylor. “We are hopeful insights from this study will help other neurologists and geneticists in accurate diagnosis and better management of this novel disorder.”

Others involved in the study include Laurie A. Robak, Gail Demmler-Harrison, Emily C. Pao, Audrey E. Squire, Savannah Michels, Julie S. Cohen, Anne Comi, Paolo Prontera, Alberto Verrotti di Pianella, Giuseppe Di Cara, Livia Garavelli, Stefano Giuseppe Caraffi, Carlo Fusco, Roberta Zuntini, Kendall C. Parks, Elliott H. Sherr, Mais O.Hashem, Sateesh Maddirevula, Fowzan S. Alkuraya, Isphana A. F. Contractar, Jennifer E. Neil, Christopher A. Walsh, and Robin D. Clark. They were affiliated with one or more of the following institutions: Baylor College of Medicine, the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital, University of Utah, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Kennedy Krieger Institute, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, University and Hospital of Perugia, Italy; Azienda USL-IRCCS di Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy; University of California in San Francisco, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, McNair Medical Institute, The Robert and Janice McNair Foundation, Loma Linda University, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, Seattle, Brotman-Baty Institute for Precision Medicine, Seattle. The funding for the research reported in this publication was supported by Jordan’s Guardian Angels, the Brotman-Baty Institute, and the Sunderland Foundation, NINDS grant R01NS035129, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Child Neurology Society and Foundation, the Mark A. Wallace Endowment, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the McNair Medical Institute at The Robert and Janice McNair Foundation, the European Reference Network on Rare Congenital Malformations and Rare Intellectual Disability ERN-ITHACA partnership.